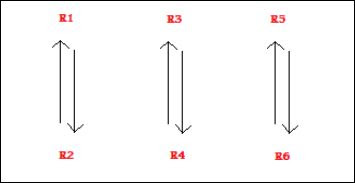

Today we are discussing a drill/technique for youth soccer players to prevent an opponent from getting ball before the goal post. This drill is known as 1v1 to Goal. The picture below is showing players positions and below the picture, the method is discussed to show how this drill should be practiced.

Rules:

After each attacking sequence, the attacker becomes the goalkeeper, the goalkeeper becomes the defender, the defender becomes the attacker.

Coaching Points:

Rules:

- B1 passes to R1, B1 tries to prevent R1 from scoring in the small goal

- Players will switch roles after each round.

After each attacking sequence, the attacker becomes the goalkeeper, the goalkeeper becomes the defender, the defender becomes the attacker.

Coaching Points:

- Defender runs quickly out to meet the attacker

- As defender gets closer to the attacker, they must start to slow down